Abstract

Summary

In a highly representative sample of young adult Swedish men (n = 2,384), we demonstrate that physical activity during childhood and adolescence was the strongest predictor of calcaneal bone mineral density (BMD), and that peak bone mass was reached at this site at the age of 18 years.

Introduction

The purpose of the present study was to determine if physical activity during growth is associated with peak calcaneal BMD in a large, highly representative cohort of young Swedish men.

Methods

In this study, 2,384 men, 18.3 ± 0.3 (mean ± SD) years old, were included from a population attending the mandatory tests for selection to compulsory military service in Sweden. BMD (g/cm2) of the calcaneus was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Training habits were investigated using a standardized questionnaire.

Results

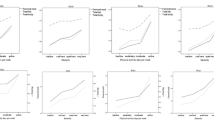

Regression analysis (with age, height, weight, smoking, and calcium intake as covariates) demonstrated that history of regular physical activity was the strongest predictor and could explain 10.1% of the variation in BMD (standardized β = 0.31, p < 0.001). A regression model with quadratic age effect revealed maximum BMD at 18.4 years.

Conclusions

We found that history of physical activity during growth was the strongest predictor of peak calcaneal BMD in young men.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Genant HK, Cooper C, Poor G et al (1999) Interim report and recommendations of the World Health Organization task-force for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 10:259–264

Nguyen TV, Eisman JA (2000) Genetics of fracture: challenges and opportunities. J Bone Miner Res 15:1253–1256

Johansson C, Black D, Johnell O et al (1998) Bone mineral density is a predictor of survival. Calcif Tissue Int 63:190–196

Browner WS, Seeley DG, Vogt TM et al (1991) Non-trauma mortality in elderly women with low bone mineral density. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet 338:355–358

Kanis JA (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. Osteoporos Int 4:368–381

Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC Jr (1990) The contribution of bone loss to postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 1:30–34

Kelly PJ, Morrison NA, Sambrook PN et al (1995) Genetic influences on bone turnover, bone density and fracture. Eur J Endocrinol 133:265–271

Rizzoli R, Bonjour JP, Ferrari SL (2001) Osteoporosis, genetics and hormones. J Mol Endocrinol 26:79–94

Giguere Y, Rousseau F (2000) The genetics of osteoporosis: ‘complexities and difficulties’. Clin Genet 57:161–169

Pocock NA, Eisman JA, Hopper JL et al (1987) Genetic determinants of bone mass in adults. A twin study. J Clin Invest 80:706–710

Chilibeck PD, Sale DG, Webber CE (1995) Exercise and bone mineral density. Sports Med 19:103–122

Kannus P, Haapasalo H, Sankelo M et al (1995) Effect of starting age of physical activity on bone mass in the dominant arm of tennis and squash players. Ann Intern Med 123:27–31

Welten DC, Kemper HC, Post GB et al (1994) Weight-bearing activity during youth is a more important factor for peak bone mass than calcium intake. J Bone Miner Res 9:1089–1096

Bass S, Pearce G, Bradney M et al (1998) Exercise before puberty may confer residual benefits in bone density in adulthood: studies in active prepubertal and retired female gymnasts. J Bone Miner Res 13:500–507

Lorentzon M, Mellstrom D, Ohlsson C (2005) Association of amount of physical activity with cortical bone size and trabecular volumetric BMD in young adult men: the GOOD study. J Bone Miner Res 20:1936–1943

MacKelvie KJ, Khan KM, McKay HA (2002) Is there a critical period for bone response to weight-bearing exercise in children and adolescents? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 36:250–257

Tobias JH, Steer CD, Mattocks CG et al (2007) Habitual levels of physical activity influence bone mass in 11-year-old children from the United Kingdom: findings from a large population-based cohort. J Bone Miner Res 22:101–109

Bradney M, Pearce G, Naughton G et al (1998) Moderate exercise during growth in prepubertal boys: changes in bone mass, size, volumetric density, and bone strength: a controlled prospective study. J Bone Miner Res 13:1814–1821

Lorentzon M, Mellstrom D, Ohlsson C (2005) Age of attainment of peak bone mass is site specific in Swedish men—the GOOD study. J Bone Miner Res 20:1223–1227

Bonjour JP, Theintz G, Law F et al (1994) Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int 4(Suppl 1):7–13

Slosman DO, Rizzoli R, Pichard C et al (1994) Longitudinal measurement of regional and whole body bone mass in young healthy adults. Osteoporos Int 4:185–190

Vogel JM (1988) The clinical relevance of calcaneus bone mineral measurements: a review. Bone Miner 5:35–58

Kullenberg R, Falch JA (2003) Prevalence of osteoporosis using bone mineral measurements at the calcaneus by dual X-ray and laser (DXL). Osteoporos Int 14:823

Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS et al (1995) Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med 332:767–773

Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC et al (1993) Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet 341:72–75

Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H (1996) Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 312:1254–1259

Miller PD, Siris ES, Barrett-Connor E et al (2002) Prediction of fracture risk in postmenopausal white women with peripheral bone densitometry: evidence from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. J Bone Miner Res 17:2222–2230

Neville CE, Murray LJ, Boreham CA et al (2002) Relationship between physical activity and bone mineral status in young adults: the Northern Ireland Young Hearts Project. Bone 30:792–798

Groothausen J, Siemer H, Kemper HCG et al (1997) Influence of peak strain on lumbar bone mineral density: an analysis of 15 year physical activity in young males and females. Pediatr Exerc Sci 9:159–173

Daly RM, Bass SL (2006) Lifetime sport and leisure activity participation is associated with greater bone size, quality and strength in older men. Osteoporos Int 17:1258–1267

Bonjour JP, Theintz G, Buchs B et al (1991) Critical years and stages of puberty for spinal and femoral bone mass accumulation during adolescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 73:555–563

Theintz G, Buchs B, Rizzoli R et al (1992) Longitudinal monitoring of bone mass accumulation in healthy adolescents: evidence for a marked reduction after 16 years of age at the levels of lumbar spine and femoral neck in female subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 75:1060–1065

Fredericson M, Chew K, Ngo J et al (2007) Regional bone mineral density in male athletes: a comparison of soccer players, runners and controls. Br J Sports Med 41:664–668

Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA (2005) Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Med 35:339–361

de Klerk G, van der Velde D, van der Palen J et al (2009) The usefulness of dual energy X-ray and laser absorptiometry of the calcaneus versus dual energy X-ray absorptiometry of hip and spine in diagnosing manifest osteoporosis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 129:251–257

Gonnelli S, Cepollaro C, Gennari L et al (2005) Quantitative ultrasound and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in the prediction of fragility fracture in men. Osteoporos Int 16:963–968

Jones G, Boon P (2008) Which bone mass measures discriminate adolescents who have fractured from those who have not? Osteoporos Int 19:251–255

Blair SN, Dowda M, Pate RR et al (1991) Reliability of long-term recall of participation in physical activity by middle-aged men and women. Am J Epidemiol 133:266–275

Falkner KL, Trevisan M, McCann SE (1999) Reliability of recall of physical activity in the distant past. Am J Epidemiol 150:195–205

Slattery ML, Jacobs DR Jr (1995) Assessment of ability to recall physical activity of several years ago. Ann Epidemiol 5:292–296

Bass SL, Saxon L, Daly RM et al (2002) The effect of mechanical loading on the size and shape of bone in pre-, peri-, and postpubertal girls: a study in tennis players. J Bone Miner Res 17:2274–2280

Specker B, Binkley T, Fahrenwald N (2004) Increased periosteal circumference remains present 12 months after an exercise intervention in preschool children. Bone 35:1383–1388

Nilsson M, Ohlsson C, Mellstrom D et al (2009) Previous sport activity during childhood and adolescence is associated with increased cortical bone size in young adult men. J Bone Miner Res 24:125–133

Hasselstrom H, Karlsson KM, Hansen SE et al (2007) Peripheral bone mineral density and different intensities of physical activity in children 6–8 years old: the Copenhagen School Child Intervention study. Calcif Tissue Int 80:31–38

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

U. Pettersson and M. Nilsson contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pettersson, U., Nilsson, M., Sundh, V. et al. Physical activity is the strongest predictor of calcaneal peak bone mass in young Swedish men. Osteoporos Int 21, 447–455 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0982-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0982-2