Abstract

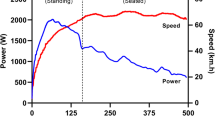

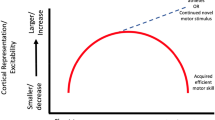

Performance in sprint exercise is determined by the ability to accelerate, the magnitude of maximal velocity and the ability to maintain velocity against the onset of fatigue. These factors are strongly influenced by metabolic and anthropometric components. Improved temporal sequencing of muscle activation and/or improved fast twitch fibre recruitment may contribute to superior sprint performance. Speed of impulse transmission along the motor axon may also have implications on sprint performance. Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) has been shown to increase in response to a period of sprint training. However, it is difficult to determine if increased NCV is likely to contribute to improved sprint performance.

An increase in motoneuron excitability, as measured by the Hoffman reflex (H-reflex), has been reported to produce a more powerful muscular contraction, hence maximising motoneuron excitability would be expected to benefit sprint performance. Motoneuron excitability can be raised acutely by an appropriate stimulus with obvious implications for sprint performance. However, at rest H-reflex has been reported to be lower in athletes trained for explosive events compared with endurance-trained athletes. This may be caused by the relatively high, fast twitch fibre percentage and the consequent high activation thresholds of such motor units in power-trained populations. In contrast, stretch reflexes appear to be enhanced in sprint athletes possibly because of increased muscle spindle sensitivity as a result of sprint training. With muscle in a contracted state, however, there is evidence to suggest greater reflex potentiation among both sprint and resistance-trained populations compared with controls. Again this may be indicative of the predominant types of motor units in these populations, but may also mean an enhanced reflex contribution to force production during running in sprint-trained athletes.

Fatigue of neural origin both during and following sprint exercise has implications with respect to optimising training frequency and volume. Research suggests athletes are unable to maintain maximal firing frequencies for the full duration of, for example, a 100m sprint. Fatigue after a single training session may also have a neural manifestation with some athletes unable to voluntarily fully activate muscle or experiencing stretch reflex inhibition after heavy training. This may occur in conjunction with muscle damage.

Research investigating the neural influences on sprint performance is limited. Further longitudinal research is necessary to improve our understanding of neural factors that contribute to training-induced improvements in sprint performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Miller J. Burst of speed. South Bend (IN): Icarus Press, 1984

Mero A, Luhtanen P, Viitaslo JT, et al. Relationship between the maximal running velocity, muscle fibre characteristics, force production and force relaxation of sprinters. Scand J Sports Sci 1981; 3: 16–22

Jacobs I, Esbjornsson M, Slyven C, et al. Sprint training effects on muscle myoglobin, enzymes, fibre types, and blood lactate. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1987; 19 (4): 368–74

Allemeier CA, Fry AC, Johnson P, et al. Effects of sprint cycle training on human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 1994; 77 (5): 2385–90

Hakkinen K, Komi PV. Electromyographic changes during strength training and detraining. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1983; 15 (6): 455–60

Hakkinen K, Komi PV, Alen M. Effect of explosive type strength training on isometric force and relaxation time, EMG and muscle fibre characteristics of leg extensor muscles. Acta Physiol Scand 1985; 125: 587–600

Hakkinen K, Komi PV. Effect of explosive type strength training on EMG and force pad characteristics of leg extensor muscles during concentric and various stretch shortening cycle exercises. Scand J Sports Sci 1985; 7: 65–76

Dietz V, Schmidtbleicher D, Noth J. Neuronal mechanisms of human locomotion. J Neurophysiol 1979; 42 (5): 1212–22

Jönhagen S, Ericson MO, Németh G, et al. Amplitude and timing of electromyographic activity during sprinting. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1996; 6: 15–21

Mero A, Komi PV. EMG, force and power analysis of sprint specific exercises. J Appl Biomech 1994; 10 (1): 1–13

Nummela A, Rusko H, Mero A. EMG activities and ground reaction forces during fatigued and non-fatigued sprinting. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1994; 26 (5): 605–9

Bernardi M, Solomonow M, Nguyen G, et al. Motor unit recruitment strategy changes with skill acquisition. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1996; 74: 52–9

Hakkinen K, Komi PV. Training-induced changes in neuromuscular performance under voluntary and reflex conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1986; 55: 147–55

Raglin JS, Koceja DM, Stager JM, et al. Mood, neuromuscular function, and performance during training in female swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1996; 28 (3): 372–7

Sleivert GG, Backus RD, Wenger HA. The influence of a strength sprint training sequence on multi joint power output. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995; 27 (12): 1655–65

Casabona A, Polizzi MC, Perciavalle V. Differences in H-Reflex between athletes trained for explosive contractions and nontrained subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1990; 61: 26–32

Kamen G, Taylor P, Beehler PJ. Ulnar and posterior nerve conduction velocity in athletes. Int J Sports Med 1984; 5 (26): 26–30

Osternig LR, Hamill J, Lander J, et al. Co-activation of sprinter and distance runner muscles in isokinetic exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1986; 18: 431–5

Saplinskas JS, Chobatas MA, Yashchaninas II. The time of completed motor acts and impulse activity of single motor units according to the training level and sport specialisation of tested persons. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1980; 20: 529–39

Mann R, Kotmel J, Herman J, et al. Kinematic trends in elite sprinters. In: Terauds J, editor. Sports biomechanics. Del Mar (CA): Academic Publishers, 1984

Ae M, Ito A, Suzuki M. The men’s 100metres. N Stud Athletics 1992; 7 (1): 47–52

Murase Y, Hoshikawa T, Yasuda N, et al. Analysis of the changes in progressive speed during 100-meter dash. In: Komi PV, editor. Biomechanics. V-B. Baltimore (MA): University Park Press, 1976: 200–207

Mero A, Komi PV. Effects of supramaximal velocity on biomechanical variables in sprinting. Int J Sport Biomech 1985; 1: 240–52

Mann R, Moran GT, Dougherty SE. Comparative electromyography of the lower extremity in jogging, running and sprinting. Am J Sports Med 1986; 14 (6): 501–10

Mero A, Komi PV. Electromyographic activity in sprinting at speeds ranging from sub maximal to supramaximal. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1987; 19 (3): 266–74

Carpentier A, Duchateau J, Hainaut K.Velocity dependent muscle strategy during plantarflexion in humans. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 1996; 6: 225–33

Schneider K, Zernicke RF, Schmidt RA, et al. Changes in limb dynamics during the practice of rapid arm movements. J Biomech 1989; 22 (8/9): 805–17

Nardone A, Schieppati M. Shift of activity from slow to fast muscle during voluntary lengthening contractions of the triceps surae muscles in humans. J Physiol 1988; 395: 363–81

Nardone A, Romano C, Schieppati M. Selective recruitment of high threshold motor units during voluntary isotonic lengthening of active muscle. J Physiol 1989; 409: 451–71

Desmedt JE, Godaux E. Fast motor units are not preferentially activated in rapid voluntary contractions in man. Nature 1977; 267 (5613): 717–9

Miyashita M, Matsui H, Miura M. The relationship between electrical activity in muscle and speed of walking and running. In: Vrendenbregt J, Wartenweiler JW, editors. Biomechanics. II. Baltimore (MA): University Park Press, 1971: 192–6

Kyröläinen H, Komi PV, Belli A. Changes in muscle activity patterns and kinetics with increasing running speed. J Strength Condition Res 1999; 13 (4): 400–6

Mero A, Komi PV. Force-, EMG-, and elasticity-velocity relationships at submaximal and supramaximal running speeds in sprinters. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1986; 55: 553–61

Suter E, Herzog W, Huber A. Extent of motor unit activation in the quadriceps muscles of healthy subjects. Muscle Nerve 1996; 19: 1046–8

Lloyd AR, Gandevia SC, Hales JP. Muscle performance, voluntary activation, twitch properties and perceived effort in normal subjects and patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain 1991; 114: 85–98

Keen DA, Yue GH, Enoka RM. Training-related enhancement in the control of motor output in elderly humans. J Appl Physiol 1994; 77 (6): 2648–58

Hoyle RJ, Holt LE. Comparison of athletes and non-athletes on selected neuromuscular tests. Aust J Sport Sci 1983; 3 (1): 13–8

Lastovka M. The conduction velocity of the peripheral motor nerves and physical training. Act Nerv Super 1969; 11 (4): 308

Lehnert VK, Weber J. Untersuchen der motorische veneleitgeschwindigkeit (NLG) des nervus ulnaris an sport. Med Sport 1975; 15: 10–4

Sleivert GG, Backus RD, Wenger HA. Neuromuscular differences between volleyball players, middle distance runners and untrained controls. Int J Sports Med 1995; 16 (5): 390–8

Upton ARM, Radford PF. Motoneurone excitability in elite sprinters. In: Komi PV, editor. Biomechanics. V-A. Baltimore (MA): University Park Press, 1975: 82–7

Appelberg B, Émonet-Dénand F. Motor units of the first superficial lumbrical muscle of the cat. J Neurophysiol 1967; 30: 154–60

Kupa EJ, Roy SH, Kandarian SC, et al. Effects of muscle fibre type and size on EMG median frequency and conduction velocity. J Appl Physiol 1995; 79 (1): 23–32

Borg J. Axonal refractory period of single short toe extensor motor units in man. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1980; 43 (10): 917–24

Moyano HF, Molina JC. Axonal projections and conduction properties of olfactory peduncle neuron’s in the rat. Exp Brain Res 1980; 39 (3): 241–8

Arasaki K, Ijima M, Nakanishi T. Normal maximal and minimal motor nerve velocities in adults determined by a collision method. Muscle Nerve 1991; 14: 647–53

Kitai TA, Sale DG. Specificity of joint angle in isometric training. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1989; 58: 744–8

Esbjornsson M, Hellsten-Westing Y, Sjodin B, et al. Muscle fibre type changes with sprint training: effect of training pattern. Acta Physiol Scand 1993; 149: 245–6

Andersson Y, Edstrom J. Motor hyper-activity resulting in diameter decrease of peripheral nerves. Acta Physiol Scand 1957; 39: 240–5

Roy RR, Gilliam TB, Taylor JF, et al. Activity-induced morphologic changes in rat soleus nerve. Exp Neurol 1983; 80: 622–32

Edds MV Jr. Hypertrophy of nerve fibres to functionally overloaded muscles. J Comp Neurol 1950; 93: 259–75

Wedeles CHA. The effects of increasing the functional load of muscle on the composition of its motor nerve [abstract]. J Anat 1949; 83: 57

Okajima Y, Toikawa H, Hanayama K, et al. Relationship between nerve and muscle fiber conduction velocities of the same motor units in man. Neurosci Lett 1998; 253: 65–7

Güllich A, Schmidtbleicher D. MVC-induced short-term potentiation of explosive force. N Stud Athletics 1996; 11 (4): 67–81

Dietz V. Human neuronal control of automatic functional movements: interaction between central programs and afferent input. Physiol Rev 1992; 72 (1): 33–69

Voight M, Dyhre-Poulsen P, Simonsen EB. Modulation of short latency stretch reflexes during human hopping. Acta Physiol Scand, 1998; 163: 181–94

Burke D. Mechanisms underlying the tendon jerk and H-reflex. In: Delwaide PJ, Young RR, editors. Clinical neurophysiology in spasticity. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1985: 55–62

Dietz V. Contribution of spinal stretch reflexes to the activity of leg muscles in running. In: Taylor A, Prochazka A, editors. Muscle receptors and movement. London: MacMillan, 1981: 339–46

Nichols TR, Houk JC. Improvement in linearity and regulation of stiffness that results from actions of the stretch reflex. J Neurophysiol 1976; 39: 119–42

Rochcongar P, Dassonville J, Le Bars R. Modification of the Hoffman reflex in function of athletic training. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1979; 40: 165–70

Maffiuletti NA, Martin A, Babault N, et al. Electrical and mechanical Hmax-Mmax ratio in power- and endurance-trained athletes. J Appl Physiol 2001; 90: 3–9

Buchthal F, Schmalbruch H. Contraction times of twitches evoked by H-reflexes. Acta Physiol Scand 1970; 80: 378–82

Almeida-Silveira M, Pérot C, Goubel F. Neuromuscular adaptations in rats trained bymuscle stretch shortening. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1996; 72: 261–6

Carp JS, Wolpaw JR. Motoneuron plasticity underlying operantly conditioned decrease in primate H-reflex. J Neurophysiol 1994; 72 (1): 431–42

Rothwell JC. Control of human voluntary movement. 2nd ed. London: Chapman and Hall, 1995

Goode DJ, Van Hoven J. Loss of patellar and achilles tendon reflexes in classical ballet dancers [letter]. Arch Neurol 1982; 39 (5): 323

Nielsen J, Crone C, Hultborn H. H-reflexes are smaller in dancers from Royal Danish Ballet then in well-trained athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1993; 66: 116–21

Nielsen J, Kagamihara Y. The regulation of presynaptic inhibition during co-contraction of antagonistic muscles in man. J Physiol 1993; 464: 575–93

Seagrave L. Introduction to sprinting. N Stud Athletics 1996; 11 (2–3): 93–113

Koceja DM, Kamen G. Conditioned patella tendon reflexes in sprint and endurance trained athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1988; 20 (2): 172–7

Kamen G, Kroll W, Zigon ST. Exercise effects upon reflex time components in weight lifters and distance runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1981; 13 (3): 198–204

Kyröläinen H, Komi PV. Neuromuscular performance of the lower limbs during voluntary and reflex activity in power and endurance trained athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1994; 69: 223–39

Evatt ML, Wolf SL, Segal RL. Modification of human spinal stretch reflexes: preliminary studies. Neurosci Lett 1989; 105: 350–5

Wolf SL, Segal RL, Hetner ND, et al. Contralateral and long latency effects of human biceps brachii stretch reflex conditioning. Exp Brain Res 1995; 107: 96–102

Butler AJ, Yue G, Darling WG. Variations in soleus H-reflexes as a function of plantar flexion torque in man. Brain Res 1993; 632: 95–104

Verrier MC. Alterations in H-reflex by variations in baseline EMG excitability. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1985; 60: 492–9

Meunier S, Peirrot-Deseilligny E. Gating of the afferent reflex volley of the monosynaptic stretch reflex during movement in man. J Physiol 1989; 419: 753–63

Stein RB, Hunter IW, LaFontaine SR, et al. Analysis of short latency reflexes in human elbow flexor muscles. J Neurophysiol 1995; 71 (5): 1900–11

Gollhofer A, Schopp A, Rapp W, et al. Changes in reflex excitability following isometric contraction in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1998; 77 (1–2): 89–97

Trimble MH, Harp SS. Postexercise potentiation of the H-reflex in humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998; 30 (6): 933–41

Hamada T, Sale DG, MacDougall JD. Postactivation potentiation in endurance trained male athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000; 32 (3): 403–11

Costill DL, Daniels J, Evans W, et al. Skeletal muscle enzymes and fiber composition in male and female track athletes. J Appl Physiol 1976; 40: 149–54

Romano C, Scheippati M. Reflex excitability of human soleus motoneurons during voluntary or lengthening contractions. J Physiol 1987; 390: 271–84

Funase K, Imanaka K, Nishihira Y, et al. Threshold of the soleus muscle H-reflex is less sensitive to the change in excitability of the motoneuron pool during plantarflexion or dorsiflexion in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1994; 69: 21–5

Nakazawa K, Yano H, Satoh H, et al. Differences in stretch reflex responses of elbow flexor muscles during shortening, lengthening and isometric contractions. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1998; 77: 395–500

Zehr EP, Stein RB. What functions do reflexes serve during human locomotion? Prog Neurobiol 1999; 58: 185–205

Gottlieb GL, Agarwal GC, Jaeger RJ. Response to sudden torques about the ankle in man. IV a functional role of α-γ linkage. J Neurophysiol 1981; 46 (1): 179–90

Komi PV. Training of muscle strength and power: interaction of neuromotoric, hypertrophic and mechanical factors. Int J Sports Med, 1986; 7 Suppl.: 10

Komi PV. Stretch shortening cycle. In: Komi PV, editor. Strength and power and sport. London: Blackwell Science Ltd, 1992: 169–79

Voight M, Chelli F, Frigo C. Changes in the excitability of soleus muscle short latency stretch reflexes during human hopping after 4 weeks of hopping training. Acta Physiol Scand 1988; 163: 181–94

Hoffer JA, Andreassen S. Regulation of soleus muscle stiffness in premamillary cats: intrinsic and reflex components. J Neurophysiol 1981; 45: 267–85

Locatelli E. The importance of anaerobic glycolysis and stiffness in the sprints (60, 100, 200 metres). N Stud Athletics 1996; 11 (2–3): 121–5

Chelly SM, Denis C. Leg power and hopping stiffness: relationship with sprint running performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001; 33 (2): 326–333

Simonsen EB, Thomsen L, Klausen K. Activity of mono- and biarticular leg muscles during sprint running. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1985; 54: 524–32

Moritani T, Oddsson L, Thorstensson A. Differences in modulation of the gastrocnemius and soleus H-reflexes during hopping in man. Acta Physiol Scand 1990; 138: 575–6

Capaday C, Stein RB. Difference in the amplitude of the human soleus H-reflex during walking and running. J Physiol 1987; 392: 513–22

Edamura M, Yang JF, Stein RB. Factors that determine the magnitude and time course of human H-reflexes in locomotion. J Neurosci 1991; 11 (2): 420–7

Gandevia SC, Allen GM, McKenzie DK. Central fatigue: critical issues, quantification and practical implications. In: Gandevia SC, Enoka RM, McComas AJ, et al., editors. Fatigue: neural and muscular mechanisms New York (NY): Plenum, 1995: 495–514

Grimby L, Hannerz J, Borg J, et al. Firing properties of single human motor units on maintained maximal voluntary effort. In: Porter R, Whelan J, editors. Human muscle fatigue: physiological mechanisms. London: Pitman Medical, 1981: 157–77 (Ciba Foundation symposium 82)

Gandevia SC, Allen GM, Butler JE, et al. Supraspinal factors in human muscle fatigue: evidence for suboptimal output from the motor cortex. J Physiol 1996; 490 (2): 529–36

Miller RG, Moussavi RS, Green AT, et al. The fatigue of rapid repetitive movements. Neurology 1993; 43 (4): 755–61

Windhorst U, Boorman G. Overview: potential role of segmental motor circuitry in muscle fatigue. Adv Exp Med Biol 1995; 384: 241–58

Schlicht W, Naretz W, Witt D, et al. Ammonia and lactate: differential information on monitoring training load in sprint events. Int J Sports Med 1990; 11 Suppl. 2: S85-S90

McFarlane B. Speed... a basic and advanced technical model. Track Tech 1994 126: 4016–20

Mero A, Peltola E. Neural activation fatigued and non-fatigued conditions of short and long sprint running. Biol Sport 1989; 6 (1): 43–58

Horita T, Komi PV, Nicol C, et al. Stretch shortening cycle fatigue: interactions among joint stiffness, reflex and muscle mechanical performance in the drop jump. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1996; 73: 393–403

Avela J, Kyrolainen H, Komi PV, et al. Reduced reflex sensitivity persists several days after long lasting stretch shortening exercise. J Appl Physiol 1999; 86 (4): 1292–300

Sinoway LI, Hill JM, Pickar JG, et al. Effects of contraction and lactic acid discharge on group III muscle afferents in cats. J Neurophysiol 1993; 69: 1053–9

Mense S. Nervous outflow from skeletal muscle following chemical noxious stimuli. J Physiol 1977; 267: 75–88

Francis C, Coplon J. Speed trap: inside the biggest scandal in Olympic history. London: Grafton Books, Collins, 1991

Penfold L, Jenkins D. Training for speed. In: Reaburn P, Jenkins D, editors. Training speed and endurance. St Leonards (NSW): Allen and Unwin, 1996: 24–41

Harridge SD, White MJ. A comparison of voluntary and electrically evoked isokinetic plantar flexion torque in males. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1993; 66: 343–8

Gandevia SC, Herbet R, Leeper JB. Voluntary activation of human elbow flexor muscles during maximal concentric contractions. J Physiol 1998; 512: 595–602

James C, Sacco P, Jones DA. Loss of power during fatigue of human leg muscles. J Physiol 1995; 484: 237–46

Kroon GW, Naeije M. Recovery following exhaustive dynamic exercise in the human biceps muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1988; 58: 228–32

Kroon GW, Naeije M. Recovery of the human biceps electromyogram after heavy eccentric, concentric or isometric exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1991; 63: 444–8

Friden J, Seger J, Ekblom B. Sublethal muscle fibre injuries after high-tension anaerobic exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1988; 57: 360–8

Bigland-Ritchie BR, Dawson NJ, Johansson RS, et al. Reflex origin for the slowing of motoneuron rates in fatiguing human voluntary contractions. J Physiol 1986; 379: 451–9

Saxton JM, Clarkson PM, James R, et al. Neuromuscular dysfunction following eccentric exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995; 27 (8): 1185–93

Buchthal F, Schmalbruch H. Contraction times and fiber types in intact muscle. Acta Physiol Scand 1970; 79: 435–52

Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA, Canepari M, et al. Specific contributions of various muscle fibre types to human muscle performance: an in vitro study. J Electroencephalogr Kinesiol 1999; 9: 87–95

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ross, A., Leveritt, M. & Riek, S. Neural Influences on Sprint Running. Sports Med 31, 409–425 (2001). https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200131060-00002

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200131060-00002