Abstract

Objectives:

To provide sex- and age-specific percentile values for levels of physical activity (PA) and sedentary time of European children aged 2.0–10.9 years from eight European countries (Sweden, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Cyprus, Spain, Belgium and Estonia).

Methods:

Free-living PA and sedentary time were objectively assessed using ActiGraph GT1M or ActiTrainer activity monitors in all children who had at least 3 days' worth of valid accelerometer data, with at least 8 h of valid recording time each day. The General Additive Model for Location Scale and Shape was used for calculating percentile curves.

Results:

Reference values for PA and sedentary time in the European children according to sex and age are displayed using smoothed percentile curves for 7684 children (3842 boys and 3842 girls). The figures show similar trends in boys and girls. The percentage of children complying with recommendations regarding moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) is also presented and varied considerably between sexes and country. For example, the percentage of study participants who were physically active (as assessed by MVPA) for 60 or more minutes per day ranged from 2.0% (Cyprus) to 14.7% (Sweden) in girls and from 9.5% (Italy) to 34.1% (Belgium) in boys.

Conclusion:

This study provides the most up-to-date sex- and age-specific reference data on PA in young children in Europe. The percentage compliance to MVPA recommendations for these European children varied considerably between sexes and country and was generally low. These results may have important implications for public health policy and PA counselling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Physical activity (PA) has assumed an increasingly prominent role in health promotion efforts given the childhood obesity epidemic. Consequently, assessing levels of regular PA and sedentary behaviour among children has become an important public health surveillance activity. Currently, the most important official reports about PA levels in European children have been based on data obtained through questionnaires.1, 2, 3 However, there is no established PA questionnaire for use in children and even the most widely used PA questionnaires, such as the International Physical Activity Questionnaire4,5 developed as an international standard questionnaire to monitor PA across diverse adult populations may be subject to recall bias, social desirability and misinterpretation. As questionnaires are too imprecise in the assessment of PA and given the advances made in this area over the last 10–15 years, objective methods should be favoured in large-scale studies or for surveillance purposes.6, 7, 8 For purposes of monitoring and surveillance, accelerometers provide a reasonable compromise between validity, reliability, ease of administration and cost.9 As such accelerometry is considered as the reference method for measuring PA and sedentary behaviour of children in free-living conditions.10 Until recently, no large representative set of accelerometer data existed to describe PA behaviour especially in young European children. In response, the International Children’s Accelerometry Database (http://www.mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk/research/studies/icad/) was established to pool data from 14 studies collected between 1998 and 2009 comprising 20 871 children (4–18 years). Time spent in moderate and vigorous PA and sedentary time was measured using accelerometry after re-analysing raw data files and independent associations between accelerometry outcomes and measures such as waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, fasting triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and insulin were examined using meta-analysis.11 In the results, reported by Ekelund et al.,12 children accumulated a modest 30±21 min per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) and this activity was associated with all cardio-metabolic outcomes independent of sex, age, monitor wear time, time spent sedentary and waist circumference. The IDEFICS study (Identification and prevention of dietary and lifestyle-induced health effects in children and infants)13 provides an excellent opportunity to augment current data by reporting the objectively measured PA data from this large sample of children from a wider range of European countries. It will extend available data as well as allow comparison with other important European studies of childhood PA.14,15 Therefore, the aim of the present analysis is to describe PA levels and to provide sex- and- age-specific PA reference standards in European children aged 2–10 years. A General Additive Model for Location Scale and Shape developed by Rigby and Stasinopoulos16 was used to calculate percentile curves. This method is an extension of the LMS method to model the distribution of PA depending on multiple covariates while accounting for dispersion, skewness, and particularly the kurtosis of this distribution.16

Material and methods

Data collection

The IDEFICS study13 is a multi-centre, prospective cohort study on lifestyle and nutrition among children aged 2.0–10.9 years from eight European countries (Sweden, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Cyprus, Spain, Belgium and Estonia) where an intervention was embedded. Data collection for T0 (baseline) took place from September 2007 to June 2008 and for T1 (follow-up) from September 2010 to May 2011. Detailed description of IDEFICS sampling and recruitment approaches, standardisation and harmonisation process, data collection, analysis strategies, quality control activity and inclusion/exclusion criteria have been published elswhere.17 Free-living PA and sedentary time were objectively assessed using Actigraph uniaxial accelerometers (either ActiTrainer or GT1M; Actigraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA). The sensor units of both models are identical. The monitor was set to record PA in a 15 s epoch. Children were instructed to wear the accelerometer for at least 3 days (including 1 weekend day). Accelerometers were mounted on the right hip of each child by means of an elastic belt and adjusted to ensure close contact with the body. Parents were also asked to complete a daily activity or ‘non-wear’ diary during the monitoring period with instructions to record the time the accelerometer belt was attached and removed. Children were encouraged to wear the accelerometer from the moment they woke up in the morning until bedtime in the evening so that a full day of PA and sedentary time could be assessed. The Research Ethics Committees of each survey region involved approved the study and informed consent for participation in the study was signed by each parent/guardian.

From the starting-point database (18 745 children), 12 014 had some data on PA; the others (6731) either refused or the assessment was not completed for other reasons (mostly, lack of devices at the time that the child was measured). In addition, subjects were excluded from analysis if the child had chronic orthopaedic, bone or joint problems, chronic rheumatic disease, or musculoskeletal diseases, as indicated in the health and medical history questionnaire (total number of children excluded for these reasons was 332).

According to the protocol, a 15-s sampling interval (‘epoch’) was to be used in PA data collection; however, a 60-s sampling interval (the default in Actigraph software) was inadvertently used in some centres for a considerable proportion of data. Three options were considered to rectify this problem: (1) include only data recorded at 15 s (or, in a few cases, sub-multiple of 15 s) epoch or re-integrate all data to 60 s, (2) use 6, 8, or 10 h as minimum requirement of valid day, and (3) the numbers of valid weekdays (1 or 2) required in addition to at least 1 weekend day. The sample sizes following each option are shown in Table 1. Of the total of 12 014 children having at least some accelerometer data, the number of children to be included in the analysis varied from 8193 according to the most liberal criterion (at least 6 h daily, at least 1 weekend day+1 weekday, using 60 s epoch), to 3390 according to the most stringent criterion considered (at least 10 h of data, at least 1 weekend day and 2 weekdays; using 15 s epoch). First, all data were re-integrated to 60 s epoch in order to incorporate the data from Italy. Second, the decision was made to use 8 h as the lower threshold of daily wearing time as previously adopted in the HELENA study,17 thus avoiding the loss of at least 1335 participants had a 10 h rule been adopted. Finally, the requirements of at least 1 vs 2 valid weekdays (in addition to at least 1 weekend day) were contrasted. Requiring 2 weekdays would have resulted in a total sample size of 5047 (42% of all children having some accelerometer data), as opposed to 7684 (64%) with the alternative criterion. The requirement was thus set to at least 1 weekday.

The possibility of sample bias induced by an additional restriction of the sample was examined by conducting an analysis of covariance using body mass index (BMI Z-scores18) as a dependent variable. The sample was therefore divided into three categories: (1) no accelerometer data; (2) incomplete data (that is, <1 weekday and 1 weekend day of at least 8 h of recording); and (3) complete data. The effect of this categorisation, adjusted for region (two regions that later became ‘intervention’ and ‘control’ regions in each country), sex and age was negligible in size (η2=0.0002) and not statistically significant (P=0.14). Moreover, the differences were not in the expected direction: the mean BMI Z-score was 0.342 in the group of children who had complete accelerometer data and 0.282 in the group who had no data (unadjusted standardised difference, Cohen’s d=0.051). Therefore, the children having complete data had, on the average, higher BMI Z-scores than those having no accelerometry data. Similarly, children having incomplete data tended to have higher BMI, than those who had complete data (respective means: 0.383 and 0.342; Cohen’s d=0.035). Note that these effect sizes are not adjusted for possible confounders.

Given PA levels tended to be higher on weekends and for ease of presentation, PA data for weekdays and weekend days were analysed separately and then combined so that weekdays were weighted by five, weekend days by two, and the result was divided by seven as previously recommended.19 To be able to compare the results of the present study (that is, re-integrated into 60 s before analysis) with data recorded at lower epoch, a formula for converting MVPA recorded at 15 s epoch to 60 s epoch is presented in the Supplementary Information. The percentage of children complying with the 60 min MVPA recommendations was determined using the weighted-average day (that is, weekend average weighted by two and weekday weighted by five).

Accelerometer data reduction

For comparability, data reduction criteria were chosen similar to those used in the HELENA study (www.helenastudy.com).17 Namely, non-wearing time was defined as 20 min or more of consecutive zero counts and at least 8 h of wear time was necessary to constitute a valid day and be included in the final analysis. Using more restrictive criteria like those in the European Youth Heart Study15 (that is, counting >10 consecutive minutes of zero recording as non-wearing time and requiring at least 10 h daily wear time) would have resulted in a loss of data from >1000 children in the present study.

Accelerometer data were analysed using algorithms developed in R (version R 3.0.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org20). A set of add-on functions to R was developed that allowed R to automatically read in the accelerometer raw files and where necessary re-integrate any data collected to standardise epoch settings, edit the data for excluding the likely non-wearing periods and compute daily summary statistics. Two rules were used for excluding data: (1) all negative counts were replaced by missing data code and (2) periods of 20 min or more consecutive zero counts were replaced by missing data code before further analysis. The output generated by R included accelerometer counts per minute (CPM), total monitoring time and time spent sedentary and in physical activities of different intensities based on Evenson cutoffs21 (sedentary: 0–100, light: 101–2295, moderate: 2296–4011, vigorous: 4012 and more CPM).

The following dependent variables were used for the analysis: average CPM (that is, sum of daily counts divided by valid time, averaged over all ‘valid days’), MVPA (minutes spent in at least moderate activity according to Evenson cutoffs), light activity, and sedentary time. The last two were used in two versions: (1) ‘raw’ minutes, and (2) ‘adjusted’ minutes. Adjusted minutes were computed by dividing the raw minutes by wearing time and multiplying the resulting fraction by the average wearing time. Average wearing time of the final sample was 740±100 min (mean±s.d.). Data have also been analysed using other common cutoffs ie Sirard,22 Pate,23 Puyau,24 and Van Cauwenberghe.25 Results are presented in Supplementary Tables A–C.

Statistical analysis

The General Additive Model for Location Scale and Shape method is able to particularly model the kurtosis using other distributions and to include more than one covariate. We used the gamlss package (version 4.2–6) of the statistical software R (version 3.0.1).20 Different distributions, that is, the Box-Cox power exponential, the Box-Cox t or the Box-Cox Cole and Green, the normal, the power exponential and the t family distribution were fitted to the observed distribution of PA variables. Moreover, the influence of age on parameters of the considered distributions was modelled either as a constant, as a linear function, or as a cubic spline of the covariates. Goodness of fit was assessed by the Bayesian Information Criterion and Q–Q plots to select the final model including the fitted distribution of PA variables and the influence of covariates on distribution parameters. Finally, percentile curves for the 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th and 95th percentiles were calculated based on the model that showed the best goodness of fit.16,26

In order to use the same distribution for all dependent variables, it was decided to use the Box-Cox Cole and Green distribution as it was in most cases the best fitting model according to the Bayesian Information Criterion; or the difference in Bayesian Information Criterion from the best fitting model was negligible. For average CPM, the final model for both sexes considered Box-Cox Cole and Green distribution modelling log μ and log σ as a cubic spline of age, and ν as a constant. For unadjusted MVPA and light activity (both unadjusted and adjusted minutes), as well as for sedentary time (adjusted and unadjusted minutes), the final model for both sexes considered the Box-Cox Cole and Green distribution modelling log μ as a cubic spline of age, and log σ and ν as a constant. The form of the model for adjusted MVPA was different for boys and girls: for both sexes, log μ was modelled as a cubic spline of age and ν as a constant, but for boys, log σ was also a cubic spline of age but a constant for girls.

Results

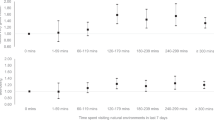

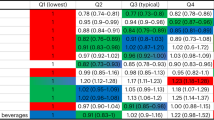

In total, data from 7684 children (3842 boys and 3842 girls) from T0 and T1 are presented in Table 2. No longitudinal data were included: for most children (N=5747), T0 values were used; the T1 values were included only if the child was newly recruited in T1, or if their PA was not measured in T0 (N=1937). The descriptive statistics of PA and sedentary time in these 2.0–10.9-year-old European children are presented in Table 3. Both CPM and MVPA were higher in boys, whereas sedentary time was higher for girls; there was no overall difference in light activity. Reference values for PA and sedentary time (Evenson cutoffs) in the European children according to sex and age are expressed using smoothed centile curves (P5, P10, P25, P50, P75, P90, P95) and are illustrated in Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. These figures show similar trends in boys and girls. Tabulated percentiles of these data are presented in the Supplementary Table A. Centile curves for PA and sedentary time were similar irrespective of whether data was adjusted or not by dividing the raw minutes by wearing time and multiplying the resulting fraction by the average wearing time (see Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7). The percentage of children complying with recommendations regarding MVPA is shown in Figure 8. The percentage compliance to MVPA recommendations for these European children varied considerably between sexes and country and was generally low with the percentage of study participants who were physically active for 60 or more minutes per day ranging from 2.0% (Cyprus) to 14.7% (Sweden) in girls and from 9.5% (Italy) to 34.1% (Belgium) in boys (Figure 8). Percentile curves for average CPM obtained from the whole sample were similar to those obtained after excluding overweight and obese children (Supplementary Tables A–C).

Discussion

The present study provides the most up-to-date sex- and age-specific data on PA in young children in Europe with important implications for public health policy and PA counselling. Although the present data should not be used as reference standards, scientists, medical and biomedical personnel and related stakeholders, children and parents will be able to compare the obtained scores with these sex- and age-specific objective measures of PA and sedentary time of European children from eight different countries. These data complement a growing literature of comparative data across a range of different health-related fitness measures such as body mass index, physical fitness, bone health and blood lipids from this unique cohort of European children (see Nagy et al., De Henauw et al., Peplies et al., De Miguel-Etayo et al.; this issue). The present analysis quantifies the magnitude and direction of sex- and age-related differences in children’s PA patterns and shows boys having higher MVPA than girls on average from the age of 5 years onwards and a larger range in MVPA. These differences in MVPA are in line with previous studies and could be largely explained by socio-cultural reasons such as more vigorous exercise outside of school, during school physical education and more participation in sports teams in boys.27

Despite the importance of PA assessment, most previous reports and fact sheets about PA levels in European youth used data obtained through questionnaires.1, 2, 3 For example, PA patterns were estimated in a cross-sectional survey of 137 593 youth (10–16 years) from the 34 (primarily European) participating countries of the 2001–2002 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study (HBSC survey) using self-completed questionnaires administered in the classroom.3 Subjects were asked how many days in the past week and in a typical week they were physically active (cumulative activity including sports, school activities, playing with friends, and walking to school) for 60 min or more. Using this approach, the percentage of study participants who were physically active for 60 or more minutes on 5 or more days per week ranged from 19.3% in France to 49.5% in the United States. Notwithstanding the usefulness of the data generated using questionnaires (for example, useful to identify, which activities were performed), such subjective approaches are heavily prone to recall bias, social desirability and misinterpretation.

Until the present analysis, no large representative set of accelerometer data existed to provide normative values especially for young European children. Notable attempts to review objectively measured PA data obtained by accelerometry from children and adolescents in Europe have been published.11,12,28 In the first attempt, data were pooled from 14 studies collected between 1998 and 2009 comprising 20 871 children (4–18 years).11 Using a meta-analysis, Ekelund et al.12 found children accumulated a modest 30±21 min per day of MVPA and this magnitude is very much in line with the data presented here from the IDEFICS study. MVPA was associated with all measured cardio-metabolic outcomes such as waist circumference, systolic blood pressure, fasting triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and insulin independent of sex, age, monitor wear time, time spent sedentary and waist circumference (when waist circumference was not the outcome).12 The subsequent study explored the proportion of European children who were assessed, based on objective assessment using accelerometry, as sufficiently active according to PA recommendations.28 In order to do this, the authors conducted systematic electronic search of studies involving European youth published up to March 2012. The analysis and interpretation of the data is difficult owing to the use of different PA thresholds lying between 1000 and 4000 counts min−1 to define MVPA. For example, up to 100% of youth may be assessed as sufficiently active when using a threshold of ~>1000–1500 CPM. Applying >2000 CPM as the cutoff, which is most frequently used, up to 87% of European children and adolescents would be considered physically active according to the current recommendations that children aged 5–18 years should engage in MVPA for a minimum of 60 min on a daily basis.29 If the cutoff would be raised to >3000 CPM, only 3–5% of the children would reach these recommendations.

The large discrepancy in outcomes released by accelerometer data is mainly due to the variety of cutoff points for MVPA among children and adolescents, hindering the definition of a clear goal towards PA promotion in Europe and beyond; standardisation of these methods is, therefore, urgently required. The results of the study by Guinhouya et al.28 illustrate the significant impact of methodological decisions on accelerometer outcome variables and consequently the observed compliance to public health guidelines in young children. For example, choosing a low cutoff can wrongly classify inactive children as active and vice versa.23 Trost et al.30 have compared an array of varying cutoffs for children and recommend Evenson’s cutoffs as the most accurate when assessing all levels of activity. Cutoffs developed for pre-school children by Van Cauwenberghe et al.25 are similar to those by Evenson for MVPA counts (Evenson:⩾585 counts per 15 s vs Van Cauwenberghe:⩾574 counts per 15 s) but ~120 counts per 15 s lower by Van Cauwenberghe for vigorous activities. However, the validity of these recommendations remains to be determined conclusively and, therefore, consensus on this subject remains elusive, although essential.

Given the recommendation30 that the Evenson’s cutoffs are the most accurate when assessing all levels of activity in young children, these cutoffs have been preferred to generate the primary normative PA data for this cohort (albeit the data using the other commonly used cutoffs can also be found in the supplementary material). Using the Evenson cutoffs PA patterns were also generated for the different countries. One must exercise caution in extrapolating this data to each respective country as the IDEFICS study is not nationally representative because each survey centre only covered a delimited geographic area within a country. Furthermore and like all studies, the present study is not without limitations. Most important of these limitations relate to the variable use of accelerometers (that is, typically less than 4 days) and in only a proportion of the IDEFICS study cohort (see Table 2) due primarily due to the prohibitive cost of purchasing sufficient accelerometer devices for the testing of as many of the IDEFICS cohort possible and avoiding any negative impact on compliance given the already significant burden for parents, teachers and the children from the large amount of data being collected on numerous occasions. Nevertheless, some interesting patterns do emerge that tend to agree with other published data. For example, the proportion of children complying with MVPA recommendations is low in Italy and Cyprus and higher in Estonia, Hungary, Germany, Sweden, Belgium and Spain (see Figure 8). This trend is in almost complete agreement with data on physical fitness published previously.31

In conclusion, accelerometry is currently considered to be the most valid method of assessing PA among children in free-living conditions. In anticipation of an even greater reliance on accelerometry for measuring movement behaviours of children, the present study provides the most up-to-date and comprehensive set of sex- and age-specific reference data on PA in children and youth. These reference values may have important implications for public health policy and PA counselling to motivate young individuals with low levels of PA to set appropriate goals and monitor individual changes in PA.

References

Carroquino-Salto MJ . Percentage of Physically Active Children and Adolescents. Fact Sheet 2.4. Report No.: RPG2_Hous_Ex1. WHO Regional Office for Europe & the European Environment and Health Information System (ENHIS): Bonn, 2009.

Cavill N, Kahlmeier S, Racioppi F . Physical Activity and Health in Europe: Evidence for Action. WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2006.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Boyce WF, Vereecken C, Mulvihill C, Roberts C et al. The Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Obesity Working Group. Comparison of overweight and obesity prevalence in school-aged youth from 34 countries and their relationships with physical activity and dietary patterns. Obesity Reviews 2005; 6: 123–132.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman A, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sport Exerc 2003; 35: 1381–1395.

Paul HL, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM . Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011; 8: 115.

Basterfield L, Adamson AJ, Parkinson KN, Maute U, Li P-X, Reilly JJ . Surveillance of physical activity in the UK is flawed: validation of the health survey for England physical activity questionnaire. Arch Dis Child 2008; 93: 1054e8.

Adamo KB, Prince SA, Tricco AC, Connor-Gorber S, Tremblay M . A comparison of indirect versus direct measures for assessing physical activity in the pediatric population: a systematic review. Int J Ped Obes 2009; 4: 2e27.

Corder K, van Sluijs EM, Wright A, Whincup P, Wareham NJ, Ekelund U . Is it possible to assess free-living physical activity and energy expenditure in young people by self-report? Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89: 862e70.

Troiano E . Large-scale applications of accelerometers: new frontier and new questions. Med Sci Sport Exerc 2007; 39: 1501.

Bornstein DB, Beets MW, Byun W, McIver K . Accelerometer derived physical activity levels of preschoolers: a meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport 2011; 14: 504e11.

Sherar LB, Griew P, Esliger DW, Cooper AR, Ekelund U, Judge K et al. International Children’s Accelerometry Database (ICAD): design and methods. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 485.

Ekelund U, Luan J, Sherar LB, Esliger DW, Griew P, Cooper C . Association of moderate to vigorous physical activity and sedentary time with cardiometabolic risk factors in children and adolescents. JAMA 2012; 307: 704–712.

Ahrens W, Bammann K, Siani A, Buchecker K, De Henauw S, Iacoviello L et al. IDEFICS consortium. The IDEFICS cohort: design, characteristics and participation in the baseline survey. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011; 35: S3–S15.

Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Martínez-Gómez D, Labayen I, Moreno LA, De Bourdeaudhuij I et al. HELENA Study Group. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in European adolescents: the HELENA study. Am J Epidemiol 2011; 174: 173–184.

Riddoch CJ, Bo Andersen L, Wedderkopp N, Harro M, Klasson-Heggebø L, Sardinha LB et al. Physical activity levels and patterns of 9- and 15-yr-old European children. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004; 36: 86–92.

Stasinopoulos DM, Rigby R . Generalized additive models for location scale and shape (GAMLSS) in R. J Stat Softw 2007; 23: 1–46.

Martinez-Gomez D, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Veiga OL, Moliner-Urdiales D, Mauro B et al. HELENA Study Group. Recommended levels of physical activity to avoid an excess of body fat in European adolescents The HELENA Study. Am J Prev Med 2010; 39: 203–211.

Cole TJ, Lobstein T . Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes 2012; 7: 284–294.

Ortega FB, Konstabel K, Pasquali E, Ruiz JR, Hurtig-Wennlöf A, Mäestu J et al. Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time during childhood, adolescence and young adulthood: a cohort study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e60871.

R Development Core Team. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Online). R Development Core Team: Vienna, Austria, (ISBN 3–900051-07–0’) http://www.R-project.org/, 2013.

Evenson KR, Cattellier D, Gill K, Ondrak K, McMurray RG . Calibration of two objective measures of PA for children. J Sports Sci 2008; 26: 1557–1565.

Sirard J, Trost SG, Pfeiffer KA, Dowda M, Pate RR . Calibration and evaluation of an objective measure of physical activity in preschool children. J Phys Act Health 2005; 3: 345–357.

Pate RR, Almeida MJ, McIver KL, Pfeiffer KA, Dowda M . Validation and calibration of an accelerometer in preschool children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14: 2000–2006.

Puyau MR, Adolph AL, Vohra FA, Butte NF . Validation and calibration of physical activity monitors in children. Obes Res 2002; 10: 150–157.

Van Cauwenberghe E, Labarque V, Trost SG, de Bourdeaudhuij I, Cardon G . Calibration and comparison of accelerometer cut points in preschool children. Int J Pediatr Obes 2011; 6: 582–589.

Cole TJ, Stanokevic S, Stocks J, Coates A, Hankinson J, Wade A . Age-and size-related reference ranges: a case study of spirometry through childhood and adulthood. Stat Med 2009; 28: 880–898.

Sallis JF, Zakarian JM, Hovell MF, Hofstetter CR . Ethnic, socioeconomic, and sex differences in physical activity among adolescents. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49: 125–134.

Guinhouya BC, Samouda H, de Beaufort C . Level of physical activity among children and adolescents in Europe: a review of physical activity assessed objectively by accelerometry. Public Health 2013; 127: 301–311.

Strong WB, Malina R, Blimkie CJ, Daniels SR, Dishman RK, Gutin B et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J Pediatr 2005; 146: 732e7.

Trost SG, Loprinzi PD, Moore R, Pfeiffer KA . Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011; 43: 1360–1368.

Olds T, Tomkinson G, Leger L, Cazorla G . Worldwide variation in the performance of children and adolescents: an analysis of 109 studies of the 20-m shuttle run test in 37 countries. J Sports Sci 2006; 24: 1025–1038.

Acknowledgements

This work has been done as part of the IDEFICS Study (http://www.idefics.eu). We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the European Community within the Sixth RTD Framework Programme Contract No. 016181 (FOOD). We thank the IDEFICS children and their parents who generously volunteered and participated in this project. We are also grateful to the Volkswagen Foundation that financially supported the production of this supplement.

STATEMENT OF ETHICS

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during this research. Approval by the appropriate Ethics Committees was obtained by each of the eight centres doing the fieldwork. Study children did not undergo any procedure before both they and their parents had given consent for examinations, collection of samples, subsequent analysis and storage of personal data and collected samples. Study subjects and their parents could consent to single components of the study while abstaining from others.

DISCLAIMER

The information in this document reflects the authors' view and is provided as is.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Konstabel, K., Veidebaum, T., Verbestel, V. et al. Objectively measured physical activity in European children: the IDEFICS study. Int J Obes 38 (Suppl 2), S135–S143 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.144

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.144

This article is cited by

-

The association between leisure-time physical activity and blood pressure changes from adolescence to young adulthood: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

KLB and NOX4 expression levels as potential blood-based transcriptional biomarkers of physical activity in children

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Identifikation motorischer Defizite im Kindergarten aus der Sicht von österreichischen Kindergartenpädagog:innen

Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung (2023)

-

Classroom-based physical activity and teachers’ instructions on students’ movement in conventional classrooms and open learning spaces

Learning Environments Research (2023)

-

Gender differences in the distribution of children’s physical activity: evidence from nine countries

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2023)