Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To assess the role of television as tool for childhood obesity prevention.

METHOD:Review of the available literature about the relationship between television and childhood obesity, eating habits and body shape perception.

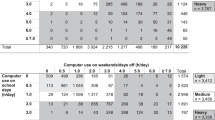

RESULTS: The reviewed studies showed the following: television watching replaces more vigorous activities; there is a positive correlation between time spent watching television and being overweight or obese on populations of different age; obesity prevalence has increased as well as the number of hours that TV networks dedicate to children; during the last 30 y, the rate of children watching television for more than 4 h per day seems to have increased; children are exposed to a large number of important unhealthy stimulations in terms of food intake when watching television; over the last few years, the number of television food commercials targeting children have increased especially when it comes to junk food in all of its forms; the present use of food in movies, shows and cartoons may lead to a misconception of the notion of healthy nutrition and stimulate an excessive intake of poor nutritional food; and obese subjects shown in television programmes are in a much lower percentage than in real life and are depicted as being unattractive, unsuccessful and ridiculous or with other negative traits and this is likely to result in a worsening of the isolation in which obese subjects are often forced. The different European countries have different TV legislations.

CONCLUSION: The usual depiction of food and obesity in television has many documented negative consequences on food habits and patterns. The different national regulations on programs and advertising directed to children could have a role in the different prevalence of childhood obesity in different European countries. Television could be a convenient tool to spread correct information on good nutrition and obesity prevention.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Guillaume M, Lissau I . Epidemiology. In: Burniat W, Cole T, Lissau I, Poskitt EME (eds). Child and Adolescent Obesity: Causes and Consequences, Prevention and Management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp 28–49.

Bouchard C . Genetic of human obesity: recent results from linkage studies. J Nutr 1997; 127: S1887–1890.

Dietz WH, Gortmaker SL . Do we fatten our children at the television set? Obesity and television viewing in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 1985; 75: 807–812.

Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH . Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1996; 150: 356–362.

Crespo CJ, Smit E, Troiano RP, Bartlett SJ, Macera CA, Andersen RE . Television watching, energy intake, and obesity in US children: results from the 3rd National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001; 155: 360–365.

Robinson T, Hammer L, Killen J, Kraemer H, Wilson D, Hayward C, Barr Taylor C . Does television viewing increase obesity and reduce physical activity: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses among adolescent girls. Pediatrics 1993; 81: 273–280.

Dietz WH, Strasburger VC . Children, adolescents and television. Curr Probl Pediatr 1991; 21: 8–31.

Story M, Faulkner P . The prime time diet: a content analysis of eating behaviour and food messages in television program content and commercials. Am J Publ Health 1990; 6: 738–774.

Sorrisi e Canzoni TV . Mondadori ed. 28 February 2004; 9: 147–202.

Radio Times. BBC Worldwide Ltd. 〈http://www.radiotimes.com/〉.

Wall Street Journal staff reporter McDonald's becomes first outside sponsor on the Disney Channel. Wall Street J, 2002; 26: B8.

Proctor M, Moore L, Gao D, Cuppler L, Bradle M, Hood M, Ellison R . Television viewing and change in body fat from preschool to early adolescence: The Framingham Children's Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27: 827–833.

Robinson TN . Reducing children's television to prevent obesity: a randomised controlled trial. JAMA 1999; 282: 1561–1567.

Certain LK, Kahn RS . Prevalence, correlates, and trajectory of television viewing among infants and toddlers. Pediatrics 2002; 109: 634–642.

Woodard DH, Gridina N . Media in the home: the fifth annual survey of parents and children. Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania; 2000.

Gerbner G, Morgan M, Signorielli N . Programming health portrayals: what viewers see, say, and do. In: Pearl D, Boutherilet L, and Lazar J (eds). Television and Behavior: Ten Years of Scientific Progress and Implications for the Eighties, Volume II. Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health; 1982. pp 291–307.

Kaufman L . Prime-time nutrition. J Commun 1980; 30: 37–46.

Greenberg B, Eastin M, Hofshire L, Lachlan K, Brownell K . Portrayals of overweight and obese individuals on commercial television. Am J Publ Health 2003; 93: 1342–1348.

Fouts G, Burgraff K . Television situation-comedies: females weight, male negative comments, and audience reactions. Sex Roles 2000; 42: 925–932.

Bar-on ME . The effects of television on child health: implications and recommendations. Arch Dis Child 2000; 83: 289–292.

Valerio M, Amodio P, Dal Zio M, Vianello A, Porqueddu Zacchello G . The use of television in 2- to 8-year-old children and the attitude of parents about such use. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997; 151: 22–26.

Moreno LA, Fleta J, Mur L . Television watching and fatness in children. JAMA 1998; 280: 1230–1231.

Meltzoff AN . Imitation of televised models by infants. Child Dev 1998; 59: 1221–1229.

Caroli M, Pace F, Chiarappa S . Differences between obese and normal weight children in role identification with televised characters. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1992; 16 (Suppl 1): 39.

Bell R, Berger C, Townsend M . Portrayals of nutritional practices and exercise behaviour in popular American films, 1991–2000. Centre for Advanced Studies of Nutrition and Social Marketing, University of California, Davis: Davis, CA; 2003.

Tirodkar M, Jain A . Food messages on African American television show. Am J Pub Health 2003; 93: 439–441.

Brodie M, Foehr U, Rideout V, Baer N, Miller C, Flournoy R, Altman D . Communicating health information through the entertainment media. Health Affairs 2001; Jan/Feb: 192–199.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Soap opera viewers and health information 1999. Health styles survey executive summary, November 15, 2000 〈 http://www.cdc.gov/communication/healthsoap.htm〉 (13 January 2003).

Collins R, Elliott M, Berry S, Kanouse D, Hunter S . Entertainment television as a healthy sex educator; the impact of condom-efficacy information in an episode of friends. Pediatrics 2003; 112: 1115–1121.

Kunkel D . Children and television advertising. In: Singer D and Singer J (eds). Handbook of children and the media. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA; 2001. pp 375–393.

Kane C . TV and movie characters sell children snacks. The New York Times 8 December 2003.

Kotz K, Story M . Food advertisings during children's Saturday morning television programming: are they consistent with dietary recommendations? J Am Diet Assoc 1994; 94: 1296–1300.

Kunkel D, Gantz W . Children's television advertising in the multichannel environment. J Commun 1992; 3: 134–152.

Galts JP, White MA . The unhealthy persuader: the reinforcing value of television and children's purchase-influencing attempts at the supermarket. Child Dev 1976; 47: 1089–1096.

Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tuker KL . Relationships between use of television during meals and children's food consumption patterns. Pediatrics 2001; 107: E7.

French S, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson J, Hannan P . Fast-food restaurant use among adolescents: association with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1823–1833.

Borzekowski DL, Robinson TN . The 30-second effect: an experiment revealing the impact of television commercials on food preferences of preschoolers. J Am Diet Assoc 2001; 101: 42–46.

Lung S, Vranica S . Happy meals are no longer bringing smiles at McDonald's. Wall Street J 2003. January 31 B1.

McDonald's Corporation. McDonald's happy meal collectors. Accessed at http://www.mcdonalds.com/countries/usa/collectibles/happymeal/happymeal.htmlon February 25, 2002.

Leiber L . Commercial and character slogan recall by children aged 9 to 11 years. Budweiser Frogs versus Bugs Bunny. Berkley and San Francisco: Centre on Alcohol Advertising; 1988.

Fisher P, Schwartz M, Richards J, Goldstein A, Rojas T . Brand logo recognition by children aged 3 to 6 years: Mickey Mouse and Old Joe the Camel. JAMA 1991; 266: 3145–3148.

Lobstein T, Frelut ML . Prevalence of overweight among children in Europe. Obes Rev 2003; 4: 195–200.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caroli, M., Argentieri, L., Cardone, M. et al. Role of television in childhood obesity prevention. Int J Obes 28 (Suppl 3), S104–S108 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802802

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802802

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between television viewing and early childhood overweight and obesity: a pair-matched case-control study in China

BMC Pediatrics (2019)

-

The influence of biculturalism/integration attributes on ethnic food identity formation

Journal of Ethnic Foods (2019)

-

Prevention and Management of Childhood Obesity

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2018)

-

Prevalence, trajectories, and determinants of television viewing time in an ethnically diverse sample of young children from the UK

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2017)

-

Television food advertising to children in Slovenia: analyses using a large 12-month advertising dataset

International Journal of Public Health (2016)